Table of Contents:

Christmas, 1996: A Note to Dad

Merry Christmas! This project has been quite an undertaking, but definitely worth it. It has evolved significantly since my initial idea a few months ago. Originally, I asked Mom's opinion on writing a story where you, Dad, were in the Civil War. She suggested I write instead about someone who actually was in the Civil War - your great grandfather, John Alpheus Hatcher ("Alf").

I was concerned how much we could find out about what had happened to him. Our first lead was a book Mom had discussed with you before about Point Lookout, Maryland, the location of one of the prison camps for Confederate soldiers. Our ancestor was imprisoned there and we had this book that told us all about it! At that point, I decided to write a diary about Alf's time in prison.

Then a new challenge occurred. It seemed odd that Alf would discuss his two months in prison and neglect to talk about his year-long stint in the war itself. At that point, however, we had no idea what battles he would have fought in.

Once again, Mom, acting as project researcher, found a gem. She discovered exactly which battles Alf's unit fought in. Not only that, she found a list of everyone in his regiment, including casualties.

Now the information was really coming together. The diary exploded from an account of Alf's time in prison to his time in prison and the war. Mom continued digging up more information to give the diary credibility, like how many slaves Alf's father owned and how much the Hatcher property was worth.

Some of the information here is speculative. It didn't all necessarily happen to Alf; it isn't even realistic that he would know as much as this diary suggests (such as the details of the battles he was in and what various regiments were doing). However, any speculation is factually based. There may be stories, like the syrup incident, that didn't happen to Alf, but did actually happen to someone at some time during the war.

Before we move on, a few thanks are in order. This project wouldn't be so thorough if Mom hadn't researched it for me. Not only would I not have done as much, I wouldn't have known where to find some of it.

Then there's a rather unusual thanks - to you, Dad! Unknowingly you assisted a great deal simply by having so many Civil War books readily on hand. Well, enjoy!

A Word from Alf

Christmas 1910:

I applied for a Confederate soldier's pension in October of this year here in Richmond County, Georgia. Simeon Morris, who fought in the war with me, was there to sign it as a witness. It brought back a lot of memories.

After the war I married a widow Smith; her maiden name was Harris - Florence Maxima Harris, daughter of Benjamin F. Harris and Anna Moriah Milton. We were married by Reverend Walsh Kilpatrick of the Hephzibah Baptist Association.

Florence died just last year, on December 15, 1909. She was buried at the Linwood Cemetery, where I too plan to be buried when my time comes.

gravestone of Florence Harris Hatcher, image from findagrave.com

She had one child, named Violetta, with her former husband. Florence and I also had seven children of our own. Lila Marie was born in 1870 and had a twin, Susie, who died. After her, was Jeannie Augustus and, in 1873, Mary Anna ("Mamie"). Then came Ida, who passed away at the age of 21. Our sixth daughter was Mattie Lou, born in 1879, and our only son was Charles Volliton, born in 1881.

I worked for the Central Railroad once I got back from the war and also built a mill and ground corn for the people of the area. The people around here are still greatly affected by the war we fought nearly fifty years ago. I am no longer a young man, but the memories are still vivid.

While I fought in the war I kept a journal of my experiences. That journal, however, was lost when I became a prisoner of war. While in prison, I tried to recreate that journal, writing about my initial decision to join, the battles I fought in, and the life I led. I tried to recall the names, dates, and places as accurately as I could.

I also kept a journal through my two months in prison. After filling out my pension application, I pulled out those journals once again. I've revised them and reworked them over the last couple months and tried to put together one journal that tells what it was like to fight in the South's Second American Revolution.

I do not know what will become of these writings. I hope my family will treasure them and use them to remember the war. I myself do not ever wish to forget it. It was a time when the South stood up for its rights and fought mightily to keep them. I am honored I was a part of it, even if the result was not what I wished.

- John Alpheus Hatcher

My Father's Death

Spring 1863:

I'd begged Pa for a couple years to let me go fight for the South and defend our rights. "You gotta stay here and fight," he'd say. "You gotta fight to keep our family together. You gotta fight to keep our land. You can't do that if you get killed in the war."

It broke his heart when Ma died in September of 1861. His brother James passed away that year as well. Pa worried about my older brother Rube, who'd gone to war already. Pa realized he could no longer keep the family together. He had to ask Uncle Robert and Aunt Sarah Mercer to take in my youngest brother Robert, who was not even two when Ma died. Vol, Fannie, and William went to live with Grandpa Mercer. After Pa's death, Vol and William, along with Tim and Sarah, went to live with our uncle Robert Mercer. Fannie continued to live with Grandpa; Anna went to live with Uncle Jep Hatcher and Dena with Uncle Robert Hatcher.

Pa also owned a decent amount of property. In 1850, he owned six slaves and real estate valued at $3500. At that time, he and his older brother James ran their neighboring farms together. James had five slaves himself. In 1860, Pa owned eight slaves housed in 3 slave houses. His real estate was valued at $3000 and his personal estate at $8800.

Before he died, Pa made me promise to do all that I could to keep the family together and protect the land on which he'd devoted his life. "You're the man of the family now, son," he told me; "that means it's your family to look over now."

The Conditions of the South During the War

Winter 1863:

I struggled to keep things intact after Pa's death. Food was in short supply throughout the South. We are running low on virtually everything - meat, fruit, vegetables, flour, fats (butter, oil, lard, mayo), sugar, coffee, condiments, flavoring, vinegar, baking soda, tea, and milk. We are hurt by bad weather, lack of labor, tools, and seed. It is hard to transport what food supplies we do have since the roads are in poor shape and wagons and horses have largely gone to the Confederate Army.

Railroads can't be maintained because the only real industrial plant is the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Virginia, and all its efforts are devoted to the war.

Pretty much everything about our lives has changed because of the war. It seems that three-fourths of my clothes are made from some kind of substitute now. Sometimes people make clothes from sheets or drapes. I've heard of people making shoes from horsehide, dogskin, deerskin, pigskin, wood, leather made from worn articles, and even book bindings.

Household supplies like candles, matches, utensils, linens, needles, pins, soaps, bedding, furnishings, dishes, kettles, oil, gas for heat, coal, wood, and cutlery are all hard to get. A salary of $3000 would now buy only about $300 worth of supplies.

Medicine is either unattainable or severely overpriced. Most doctors have gone to the war.

Profiteering and bartering are both common. Government contracts do businessmen little good since they can't rely on the government to pay them.

Schools are in poor shape as well. There is a shortage of teachers, books, and supplies.

Plantations are very different. Women are running a lot of them now since so many men have gone to war. I feel like I need to go as well. Life is bleak here and I'm not sure I can protect either the farm or the family by staying.

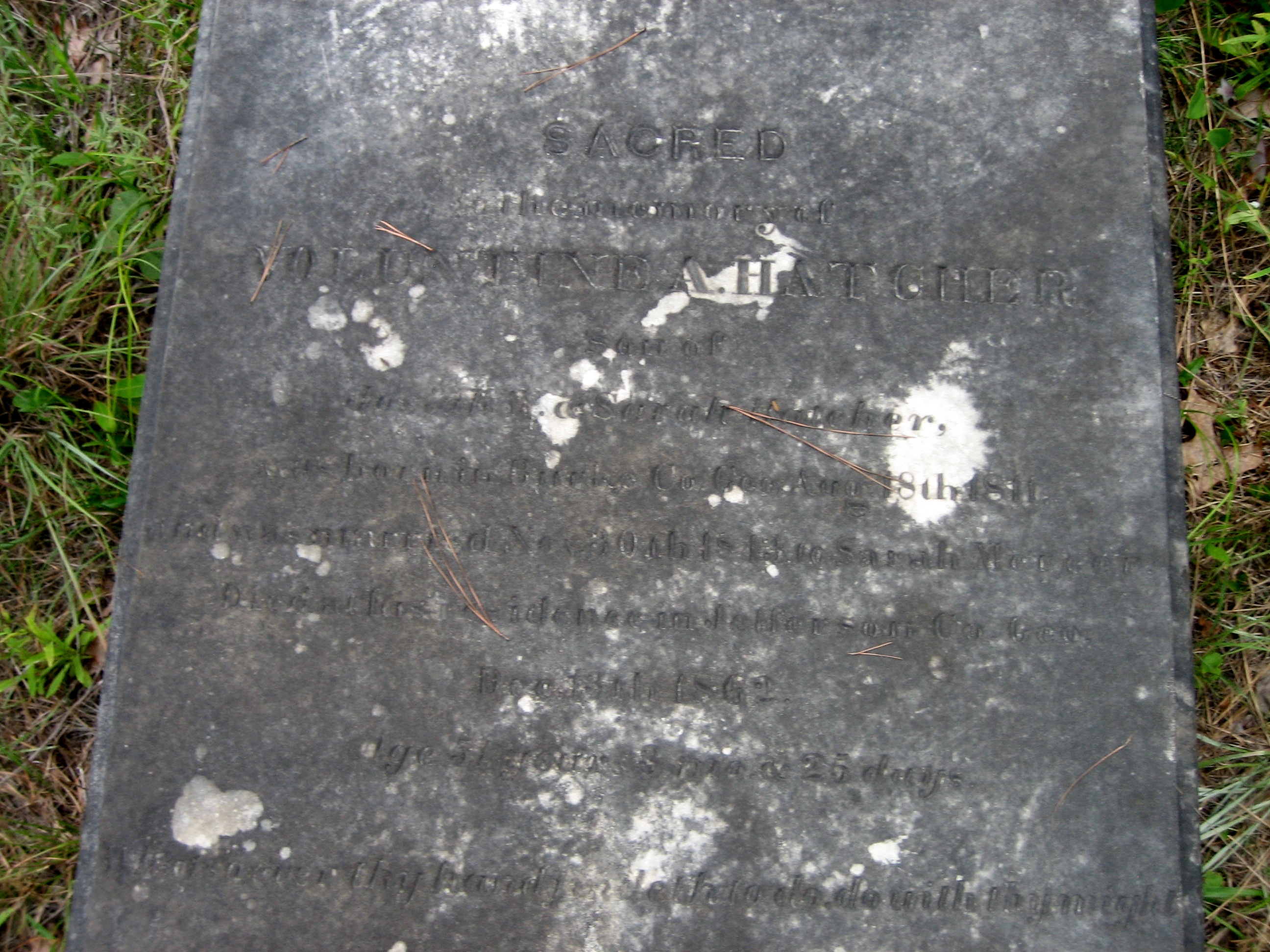

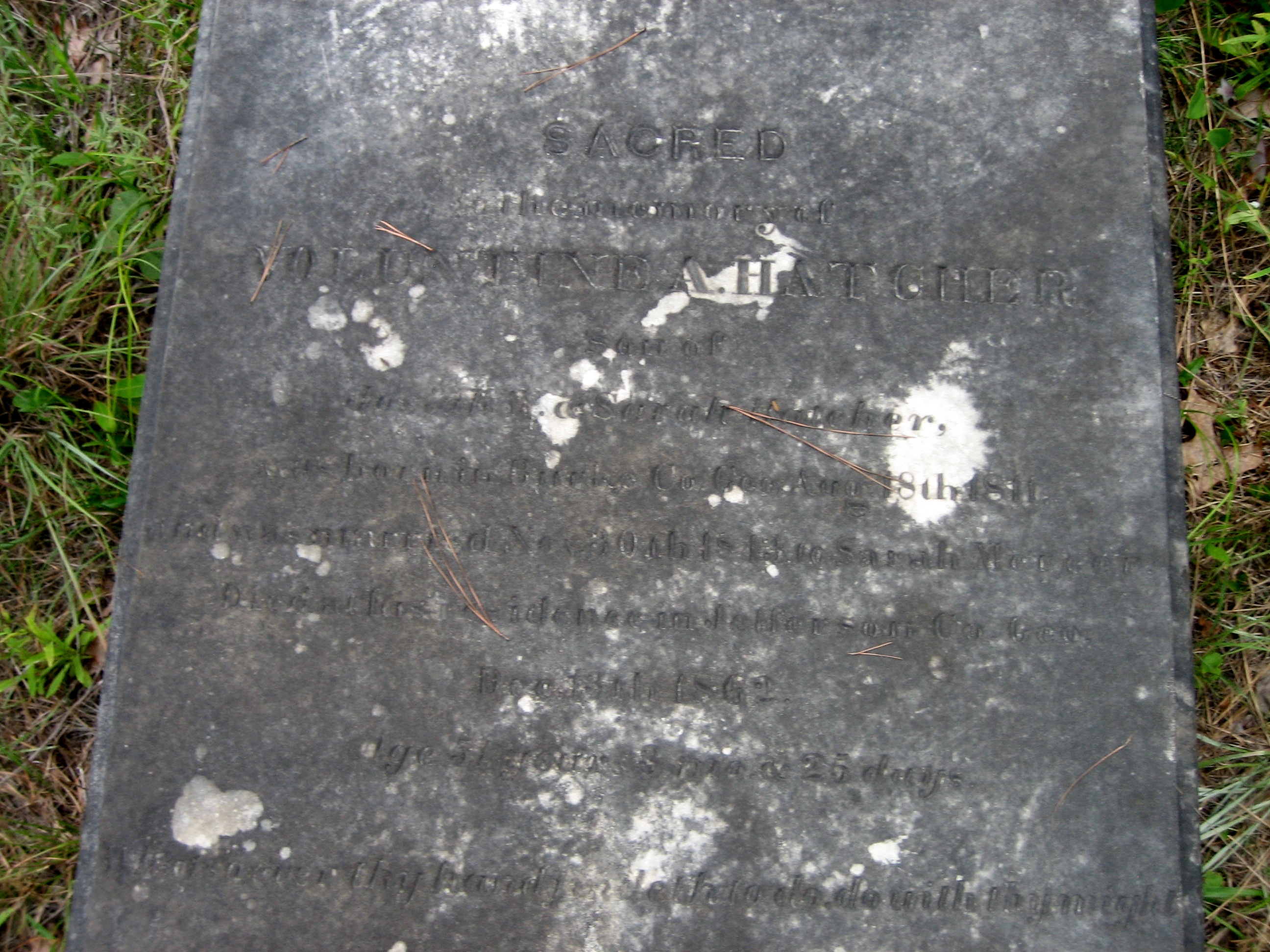

Pa's Grave

April 20, 1864:

gravestone of Voluntine Hatcher, image from findagrave.com

Sacred to the memory of

Voluntine A. Hatcher

Son of Josiah W. and Sarah Hatcher

Born in Burke Co., GA. Aug. 18, 1811

m. on Nov. 30, 1843

to Sarah Mercer

Died in his residence, Jeff. Co., GA. Dec. 13, 1862

Age 51 years 3 mo. and 25 days

"Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do with thy might"

Those were the words on my father's tombstone. I went to look at it a few days before I enlisted in the Confederate army. I prayed that Pa would understand that I had no choice but to go fight if I was to defend what mattered to him. I knew he wanted no harm to come to his family or land. I can no longer protect those hopes and wishes by staying here. If all that he accomplished is to fall, it will do so only by conquering me first.

Enlistment

April 23, 1864:

I enlisted in the Thomson Guards from Columbia County, Georgia. I was nearing my 19th birthday. I met up with them in Fredericksburg, Virginia. I became a private in F Company, 10th Regiment Georgia Volunteer Infantry. The company captains were William Johnston, William G. Green, and John T. Stovall. Captain Stovall enlisted me.

Click to see full roster for F Company, 10th Regiment Georgia Volunteer Infantry.

Most of the men in the unit enlisted May 11, 1861. However, as the ranks were thinned by disease, wounded, deaths, captures, and desertions, more would come on board on occasion.

For the men who enlisted earlier, they would go to a nearby camp for completion of the transition from civilians to soldiers. They're supposed to give everybody a physical then, but I heard they were so casual that some women managed to sneak in.

Most guys were inducted twice - first as state troops then as Confederate soldiers. Induction into national service consisted of undergoing inspection by companies by the mustering officer, pledging allegiance to the Confederacy, promising to obey orders, and swearing to abide by the Articles of War, numbering 101, which were read as the concluding feature of the induction ceremony. I didn't go through most of that because as soon as I enlisted we were off to battle.

Click here to read the Articles of War.

While in Georgia's 10th Infantry Regiment, I was in:

- Bryan's Brigade, Kershaw's Division, 1st Corps, Army of Northern Virginia, April to August 1864

- Bryan's Brigade, Kershaw's Division, Valley District, Department of Northern Virginia, August to November 1864

- Bryan's-Simms' Brigade, Kershaw's Division, 1st Corps, Army of Northern Virginia, November 1864 to April 1865

The Typical Soldier

April 24, 1864:

A lot of these guys have the same backgrounds. Most have very little education. I guess I'm lucky to have what I did on Pa's plantation. About one out of every four guys is illiterate; I've heard that in some companies as many as half the guys can't sign their names.

The South doesn't have as many soldiers as the North. One guy told me they have like two million and we've got half that. We can't let it get us down, though. We're fighting for a good cause.

The fighting force is mostly common soldiers like privates and non-commissioned officers. Only one out of ten isn't. Even then the guys that are officers are usually chosen by their own men.

Almost nobody was born in another country. 95% of us are native born and nearly all the guys in the unit were born here in the South. Most of us are volunteers as well. We pretty much came from farms and most of the guys are around my age. 75% of all common soldiers are from 18 to 30 years old.

Seeing Someone Shot

April 30, 1864:

The first time I saw someone who had been shot was not in battle, but marching toward one. We were on the way to the Wilderness Battle when I saw a dead cavalryman lying by the side of the road. He had a neat round hole through his forehead. I asked William, another guy in the company, if he had ever been shot. He told me he hadn't, but described what he'd been told it felt like. "It's winter time. You and your brother are outside playing in the snow. He scoops up a snowball, packs it together, and heaves it at you from about 12 feet away. It hits you in the upper leg and there's an immediate dull, stinging sensation that starts to spread through your leg. That's what it's like to get shot."

I saw William get shot less than a week later in the Wilderness Battle. A field surgeon came over to him and stuck his index finger in the wound to see if the bullet was still in his leg. It wasn't; it had gone completely through his leg and out the other side. The surgeon took a handkerchief, moistened it with water from a nearby creek, and placed it over the wound. Unfortunately, William didn't make it.

Like most soldiers, William was buried there on the battlefield. A wooden marker with his name and regiment marked the spot; a year or two later he would be exhumed and put in a proper military cemetery. The company officer sent a letter home and saw to it that his belongings were gathered up. Tentmates would usually write also, but it was up to the company officer to see that the next of kin was properly notified.

The Battle of the Wilderness

May 4, 1864:

It was a desperate time in the war. It was my first battle, but the general feeling among the men was that if we were not victorious, this battle could be our last. Grant was trying to move the Yankee army south toward Richmond, a move which Lee was determined to thwart. Word around camp was that Lee felt we could finish the war if we could hold Grant out of Richmond a few months and get the North feeling like the fight just wasn't worth it.

That morning the Yanks moved toward the Rapidan River; Lee moved us into a thick forest of mixed cedar and pine known locally as "the Wilderness." Our army was outnumbered at least two to one, but we were operating on interior lines and in familiar territory. A year before, the Confederate army had trapped the Union soldiers in the same location. Lee was determined to strike the Yanks while they were in the woods and preferably still on the march.

There were three roughly parallel roads that led eastward into the Wilderness - the Orange Turnpike, which ran from Orange Court House through Chancellorsville and continued to Fredericksburg; the Orange Plank Road, about two miles south of the Turnpike; and the Catharpin Road, another two or three miles farther south. All three intersected.

Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell's corps were closest. He led his men along the Turnpike. "Old Baldhead," as he was called, had a minie ball smash the bones in one of his knees at Groveton in 1862 and his leg had to be sawed away. Whenever he got on his horse he had to have an attendant help him into his saddle.

A.P. Hill, who took over Stonewall Jackson's command when he had been mortally wounded at nearby Chacellorsville almost exactly a year before, led the two divisions down the Orange Plank Road. Lee would ride with Hill.

Lieutenant General James Longstreet's corps moved up the Catharpin Road. Then there was also Lee's cavalry, led by Jeb Stuart. He had over 8000 men in three divisions.

Ewell's men halted for the night at Locust Grove, which was about two or three miles into the Wilderness. Lee and Hill were five miles southwest of Ewell at New Verdiersville (which the men called "My Dearsville"). When we settled down for camp that night we saw skulls and bones scattered everywhere, left from battle of the year before. We inspected any exposed clothing to see if they were Union or Confederate.

May 5, 1864:

Fighting began about noon. The dense underbrush and smoke from the gunfire made it difficult to see even fifty feet ahead. It was a blind hunt to the death rather than a battle. The fighting was bloody, every man for himself. Men were firing, shouting, pitching into each other with bayonets, throwing rocks, punching, and beating each other with the butts of their guns.

Like most of the guys I had a picket belt which held cartridges. Cartridges were made up of a lead bullet with a paper tube for the powder attached to one end. To load the gun you bit off the end of the paper cone, poured powder into the barrel, and rammed the bullet down after it with a ram rod. Then you took a copper cap out of your small box, capped the nipple of the rifle, and it was ready. The shooting was at pretty close range; sometimes muskets were fired at such close range that soldiers faces were burned.

The battle lines were very near each other at first and eventually no one could tell where they were. Whole units were getting lost and even firing on their own comrades. Fighting went on all day.

That night many men simply fell asleep, if they slept at all, wherever they were when they fired their last shot. All night I heard men moaning and crying for water. No one even knew, in the thick underbrush that prevented us from seeing, if those around us were friend or foe.

Battle of the Wilderness by Kurz and Allison, image from Wikipedia.org

May 6, 1864:

On the second day of fighting the Yanks were determined to drive through the middle of our army. Ewell's men began the fight at 5am. Hill's men were fighting at the crossroads, trying to secure that point. We were all waiting for Longstreet's men to arrive. Lee had already ordered Longstreet to give up on the Catharpin Road and concentrate his advances on the Orange Plank Road instead. He could relieve Hill quicker that way.

The Federals thought they had forced us into withdrawal, but they were getting entangled in the woods and slowed down. That was enough time to allow Longstreet's men to show up and take up the fight.

General John Gregg's Texas Brigade was the first of Longstreet's men to arrive. They went in to plug up the hole the Yanks were drilling through the middle of our line. They went in with nearly 700 men and lost over 400 men, but held the enemy back long enough for more of Longstreet's men to arrive.

By the end of the day we had smashed Grant's right, seized two generals and six hundred prisoners, and come close to cutting off the Union supply line. In two days, the fighting in the Wilderness had cost the Yanks 17,000 men, twice what we lost. It was said to be one of Lee's greatest victories.

That night I could hear the men all around me again. This time the screams weren't for water. They were screams of the wounded men who couldn't escape the forest fires that had been set from all the gunfire and they were burning to death.

During the Wilderness Battle we lost several men, one of who was William, whom I mentioned earlier. His name was William B. Garrett. He became a private on May 11, 1861, when most of the rest of the unit joined. On April 20, just a few days before I enlisted, he was appointed ensign on account of special gallantry. He was killed May 6 and buried on the battlefield in the Wilderness.

Benjamin Smith, another private from my unit who'd been in since the start, was wounded and captured on the same date. Albert E. Wiley, also a private since the beginning, was wounded in his right arm and had to have it amputated.

The Battle at the Spotsylvania Court House

May 7, 1864:

Lee sent some of the army farther south to Spotsylvania, anticipating that even with his heavy losses, Grant would not give up on his march to Richmond.

After the slaughter of the Wilderness Battle, both sides spent much of the day recovering and burying their dead. During the battles of the days before we couldn't even get to our wagons, so we rifled through the haversacks of dead Yankees, who had four or five days rations of hardtack and bacon.

That evening the North made a move south toward the crossroads of the Spotsylvania Court House. It was an important crossroads that lay on the route from the Wilderness to Hanover Junction. It was where Lee's principal supply lines met - the Richmond, Fredericksburg, & Potomac and the Virginia Central Railroads. It was also 12 miles closer to Richmond. Longstreet was injured so his corps was taken over by Richard Anderson, who was ordered to race to the court house. Hill was sick, so Jubal Early took his place and marched toward the court house as well.

Spotsylvania Courthouse, image from sonofthesouth.net

May 8, 1864:

Anderson's men marched hard and reached the Block House Bridge, the most important of the spans, at daybreak. It was about 8am when Anderson's men arrived at the court house.

By evening Ewell had 17,000 troops there and when darkness ended fighting for the day, we were too strong for them and Spotsylvania remained blocked.

May 9, 1864:

We spent the day digging fortifications and strengthening for an attack. By this time, Hill's men, now led by Early, were moving into line behind us.

May 10, 1864:

The Yanks slipped a brigade south across the river. However, Grant assumed we must be weak at other points in the line as well and launched a frontal attack. Three hours later we had killed about 3000 of their men.

Then they moved east to the center of our line, called "the Mule Shoe." They sent 5000 men right at this point. They drove through, where it now fell on Ewell's men as the backup, to come forth.

May 11, 1864:

The Union army was hampered by a sudden change in weather. Unseasonable heat gave way to uncomfortable cold, followed by a heavy shower of wind, rain, and hail. When they didn't attack that day, Lee decided maybe they had plans to attack further east toward Fredericksburg and find a route toward Richmond.

May 12, 1864:

Grant sent nearly 60,000 men against the Mule Shoe. Gordon's reserve division counterattacked and regained possession, but the North continued to fight, earning the Mule Shoe the new nickname of the Bloody Angle.

May 20, 1864:

It rained heavily from May 13 to May 16, but by the 18th the North came at us again. By the 20th, the Yankees gave up on frontal assaults and came at us from the west. In the end it was said the North lost 36,000 men while we lost half as many.

Reflections on My First Battle

May 1864:

After my first experience at fighting in the war I am amazed at how these guys have lived this way as long as they have. I am proud to be from the South; it is my duty to do all that I can to protect her.

There are some men who deserted and ran away during the fighting, but not many. Most of the men feel a duty to their companions in arms. Guys are more worried about being courageous than being killed; they want to make their families proud.

The other guys often compare our fighting to the Revolutionary War. Some of them talk about Washington at Valley Forge and that this is our chance to stand up and fight for what we know is right.

I guess what hit me hardest as we prepared for battle was when some of the guys were taking pieces of paper and writing their names, companies, and regiments on them and pinning them to their coats. I asked the corporal, Henry Thomas, who was from McDuffie County, why he was doing that. "In case we get killed," he said, "then someone can identify who we are."

The Battle at the North Anna Crossing

May 21, 1864:

In their continuing attempt to drive toward Richmond, the Yanks abandoned the line in front of Spotsylvania and shifted forces eastward and southward toward the North Anna Crossing, 25 miles north of Richmond. The North Anna River is a pretty stream, running between high banks, steep enough to nearly form a ravine. For the most part, the area is heavily wooded with oak and tulip trees.

North Anna Crossing, image from nps.gov

May 22, 1864:

We scurried south to get in front of them. Ewell's men took position just south of the Chesterfield Bridge, covering the railroad crossing at Hanover Junction. Anderson arrived about noon and moved his two divisions into a line extending upstream about a mile and a half from Ewell's left. Breckinridge brought two brigades from the Shenandoah and came in between Ewell and Anderson.

May 23, 1864:

Hill's men arrived and extended the line a couple of miles southwest. We had established a strong defensive position on the south bank of the North Anna River, protecting the critical railroad intersection of Hanover Junction. Lee then gave us time to recuperate from our seventeen straight days of fighting. Of course, food was scarce so that was hard. We were allowed one pint of unsifted corn meal and one-fourth of a pound of bacon for one day's ration.

The Yankees' Army of the Potomac reached the North Anna after a two-day march, approaching on a wide front. It was mid-day when they first arrived on the northern banks of the river. That afternoon they attacked us on both flanks. For two hours we raged a fierce artillery battle, even as we were hit by a pelting rainstorm. The Yanks broke across to the southern side of the North Anna before the battle was over, but Hill's men fought back hard.

May 24, 1864:

We fell back from the Chesterfield Bridge, which allowed the Yanks to cross the river unimpeded. The key to Lee's defense, however, was Ox Ford, a half-mile stretch on the south bank of the North Anna that was higher than the bank on the other side. He positioned half of Anderson's corps there, giving them strong artillery support. This allowed the rest of Anderson's men along with Ewell's and Hill's to fight from a compact five-mile-long position that converged in a V at Ox Ford, its strongest point. Grant would have to pull troops back across the river to the north side and march them around to offer support to his troops.

At 3pm, the Union soldiers drove into Ewell's corps and, despite heavy rain, fought until midnight, first capturing a section of Ewell's line, and then losing most of it back.

At the same time, another section of the Union army charged into Ox Ford, suffering heavy losses, with Lee's V strategy holding up well. The North lost nearly 2000 men in the two attacks; we lost half that. Their losses were restricted primarily to a handful of divisions; most of their men did not fight at all. After such heavy defeats in the Wilderness and Spotsylvania battles, the Yanks wouldn't fight so long this time.

May 26, 1864:

The Northern army pulled out again. They moved once again toward Richmond, marching on parallel roads to another crossing of the Pamunkey River fifteen miles downstream near Hanovertown.

May 27, 1864:

Once Lee discovered that the North had pulled out, he marched us 18 miles south to Atlee's Station along the banks of a sluggish, marsh-fringed watercourse called Totopotomoy Creek.

We were there by afternoon, well ahead of the Yanks. Lee spread the three corps out east of the station so that they blocked all approaches to Richmond from the Pamunkey River, from which the Union would be coming. We entrenched ourselves and prepared for an all-out assault.

Our leadership was in poor shape. Jackson was dead, Longstreet wounded, and Ewell was sick and gave command to Jubal Early. That meant all three army corps had changed commanders since the start of the campaign, although Hill had regained his command. Three of the army's nine infantry divisions also had new leaders, as did 14 of the 35 original brigades.

May 28, 1864:

Eight hundred green South Carolina troopers arrived and confronted the Federal infantry crossing the Pamunkey. In the next seven hours they battled, fighting in woods so dense that the cavalry had to dismount. It looked like we would win the day, but then another brigade arrived to support the North.

May 29, 1864:

Grant's men fanned out south and west, arriving around dusk at Totopotomoy Creek. Our three corps were ready on the other side. We were not in good shape, however. We couldn't make up the losses of the last month and many of the men were weak from sickness and hunger. Some had gone two days without rations and then got three biscuits and a slice of bacon to eat. Then it was another two days without food and the men got a single biscuit for their rations.

May 30, 1864:

At midday, Early was sent to intercept the Federals who were trying to march around Lee's right. Unfortunately, Early didn't bring up reserve divisions quickly enough and was beaten handily. There were about 2000 casualties to each side.

The Battle at Cold Harbor

May 31, 1864:

Once again the North began a move closer to Richmond, and once again we countered it. The race was now on for the crossroads called Cold Harbor, near the Chickahominy River. Cold Harbor was little more than a dusty intersection where five roads met. The name made no sense; there was no harbor and it certainly wasn't cold with temperatures running close to 100 degrees.

One of the five roads went eastward to White House Landing, another northwest to Bethesda Church. These two roads provided vital links, connecting Grant's army with its supply base and offering a way for Grant to extend his left flank.

Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry unit was sent about a mile east of the site of the 1862 Battle of Gaines' Mill. The North sent forces as well and clashed the same day. Fitz's cavalry was forced to abandon their defenses and were swept out of Cold Harbor, leaving their dead and wounded on the field as the North took the crossroads.

Battle of Cold Harbor, image from sonofthesouth.net

June 1, 1864:

General Lee, however, was determined to retake the crossroads. Before dawn, Anderson led four divisions, including mine - Kershaw's, to Cold Harbor. Our division and Hoke's were ordered to push back the dismounted cavalry, while the other two divisions would strike any approaching Union soldiers. We got there so quickly it was another four hours before the Yanks' foot soldiers arrived.

We were led, however, by Lawrence Keitt, who had arrived with the green South Carolina regiment the week before. Since he was a former Congressman and had a lot of power in his home state he was given charge of the brigade. He rode recklessly into battle, was toppled from his horse, and mortally wounded. The green South Carolinans ran for the rear, forcing us to give way as well. The North held the crossroads.

At 4:30 that afternoon, the North launched an attack of six divisions against Anderson's four. We made an abatis of felled trees and sharpened saplings 30 yards in front of our first line of entrenchments. When the Yanks reached the barrier they met with artillery so intense and so near that it singed the men's faces. Hundreds of men were falling on both sides. By nightfall, the Yanks had gained some ground, but lost about 2200 troops.

June 2, 1864:

Lee bolstered up our right by moving armies from the left and the center. Early's corps faced brief fighting, but rain falling heavily that afternoon curtailed operations for the day. It hailed during the night, but both rain and hail had stopped by morning.

June 3, 1864:

We waited for the Union soldiers, hiding well in our trenches we'd had plenty of time to bolster. Half of the Union army, said to be 60,000 men, charged in on the front and the flanks. We watched as they came closer and closer, anxious to open fire. Once the battle began the ground seemed to seethe like a boiling cauldron from the incessant pattering of shot which raised the dirt in geysers and spitting sand. Around 6000 Yankee soldiers fell, most in the first eight minutes of the battle. It was the bloodiest battle of the war.

For three days and nights both armies just sat, neither willing to ask for a truce to collect the wounded or bury the dead. The stench from the dead was nauseating. The dead covered more than five acres of ground about as thickly as they could be laid.

Food

Early June 1864:

Nobody enlisted in the army as a cook; we just took turns. We formed messes who tented together. It wasn't designated; it was just guys who came together. One guy would carry the coffeepot, one the stew bucket, one the frying pan, etc. We each had our own tin cup and carried coffee in our haversack.

Whenever the army halted we boiled water and shook in our coffee and would have boiled coffee in just a few minutes.

We were sometimes issued horse or mule meat as rations. When we could get ahold of beef, we would eat every scrap. Once, after slaughtering a cow, we boiled the feet to pieces, picked it clear of bones, strained it through a rough, improvised sieve, then seasoned it, mixed it with flour, and fried it with tallow. We thought cow hoofs were a delicacy.

The hardest piece of rations we were subjected to was a kind of meat called Nassua bacon. Nausea would be a better word for it. It was probably discarded ship's pork, or salt junk, or as some called it, salt horse. It was a peculiarly scaly color, spotted like a half-well case of smallpox, full of rancid odor, and utterly devoid of grease. When hung up it would double its length. It could not be eaten raw and imparted a stinking smell when boiled. It had one redeeming quality - elasticity. You could put a piece in your mouth and chew it for a long time, and the longer you chewed it the bigger it got. Then, by a desperate effort, you would gulp it down - out of sight, out of mind.

Hardtack was our standard bread ration. It was a thick cracker or biscuit often so wormy that we called them "worm castles."

Sometimes we went days without food, except maybe a few grains of corn picked up from where the horses fed. We would parch them over the glowing embers of the campfires. Once we came to a farmyard where we saw a large pot full of boiled turnips, corn, and shucks for cattle and hog feed. While it did not look so tempting, it smelled appetizing. We dipped in our tin cups and drew off some of the mess. The soft corn was really good, and, stripping the turnips off the peel, we made a meal out of it.

The Siege of Petersburg

June 15, 1864:

In the 30 days since the Wilderness battle, the Yanks lost 50,000 men, half as many as in the three previous years of struggle. Somehow, they kept going.

From Wilderness to Petersburg, image from thomaslegion.net

This time their target was Petersburg, a communications center just south of the Confederate capital. If they took it and choked off supplies, Richmond would be forced to surrender. For the first time, Lee misjudged Grant's move, rushing most of us to the outskirts of Richmond, assuming Grant would try to attack there.

When Grant's men reached Petersburg with 16,000 men we only had about 2000 soldiers south of the Appomattox River. Our army was forced to retreat, surrendering over a mile of our entrenchments.

June 18, 1864:

Over the next three days the door to Petersburg, which subsequently led to Richmond, stood open. The North waited for more soldiers to arrive and on June 17 and 18 launched an attack with an army of 75,000. Our army fought hard, though, and the Yanks only got another mile or so of our trenches. We also bought enough time to get more troops to Richmond.

June 22, 1864:

More forces arrived. We dug in for a siege. Over the months we built a labyrinth of defensive works and trenches. We worked with axes, spades, knives, and bayonets; we even used spoons and tin cans. We enclosed redans or forts as strong points for artillery and infantry. We scooped out trenches parallel to the forward line, then connected the lines with zigzagging trenches for communication. To the rear we created sunken roads along which men, guns, and wagons could move under cover from enemy guns. When shelling began from the Federals, we began constructing bombproofs with roofs made of timber and sod.

trenches at Petersburg, image from http://historyrevived.blogspot.com

July 30, 1864:

The Yanks blew up a section of the Confederate line today with an underground mine at the end of a 500-foot long tunnel built by a regiment of coal miners from Pennsylvania. When the mine exploded it scared everyone back and made a crater 30-feet deep, 70 feet wide, and 250 feet long. The Yanks' goal was to blow a line through our defenses and then rush into the town.

After the explosion, an hour went by before the Union finally stormed in with three divisions. Instead of going around the crater the bomb made, the fools went right down into it. Now they were trapped and all we had to do was line up at the rim of the crater and shoot down at them! By afternoon, they had raised their white surrender flag. We created about 4500 casualties.

August 1864:

In August, Grant attempted to take the Weldon Railroad. While they seized a small piece of the railroad, we could still get supplies to Petersburg by simply going around them.

September 4, 1864:

The Yankees fired a one-hundred-gun salute in Sherman's honor into the Confederate works at the front here in Petersburg. His march to Atlanta proved successful; the Confederates had to evacuate.

Conditions in Petersburg

Summer 1864:

The weather made life in the trenches even more miserable. We were plagued by flies and the fierce Virginia sun. We'd had no rain since Cold Harbor. It had already been hot and now became hotter than anyone could remember. At the slightest movement, inches of thick, powdery dust would well up in choking clouds.

There was a real shortage of surface water. We knew, though, if we kept digging we could get down to a layer of clay with a ready supply of cool water.

The days of July passed with the sun burning down. On all sides of me were hot, sweaty men, filthy and frightened. All the time the sounds of big guns and mortars were thumping away. Men were killed in their camps, at their meals, and in their sleep. So many men were struck daily that they became reckless, wandering around even as balls were striking around them.

The constant exposure to sun and rain, the rancid bacon and half-raw cornbread that we were issued, the filth accompanying the scarcity of clothing, the lack of opportunity for bathing or washing our clothes, the vile water, the want of rest at night, and the constant, excited anxiety, had produced and aggravated diarrhea, dysentery, dyspepsia, and slow fevers, which were wasting men away.

The biggest battle we fought in Petersburg was boredom. We went for days at a time without fighting and had nothing to do. There were men who would stand up in the trenches and taunt the enemy out of sheer boredom. Of course, some of them got shot that way.

Petersburg wasn't the only time during the war we'd fought boredom. We spent most of the time during the war trying to find things to do. We were marching and camping and trying to get enough to eat, and only once in a while were we actually fighting. Petersburg was kind of the climax of all that. It was more boring, supplies were harder to come by, and men did stupid things.

Months of this would ensue. The North swelled to 100,000 men and we fought trench warfare until March of the following year.

|