| First posted 6/12/2020; updated 7/5/2020. |

|

|

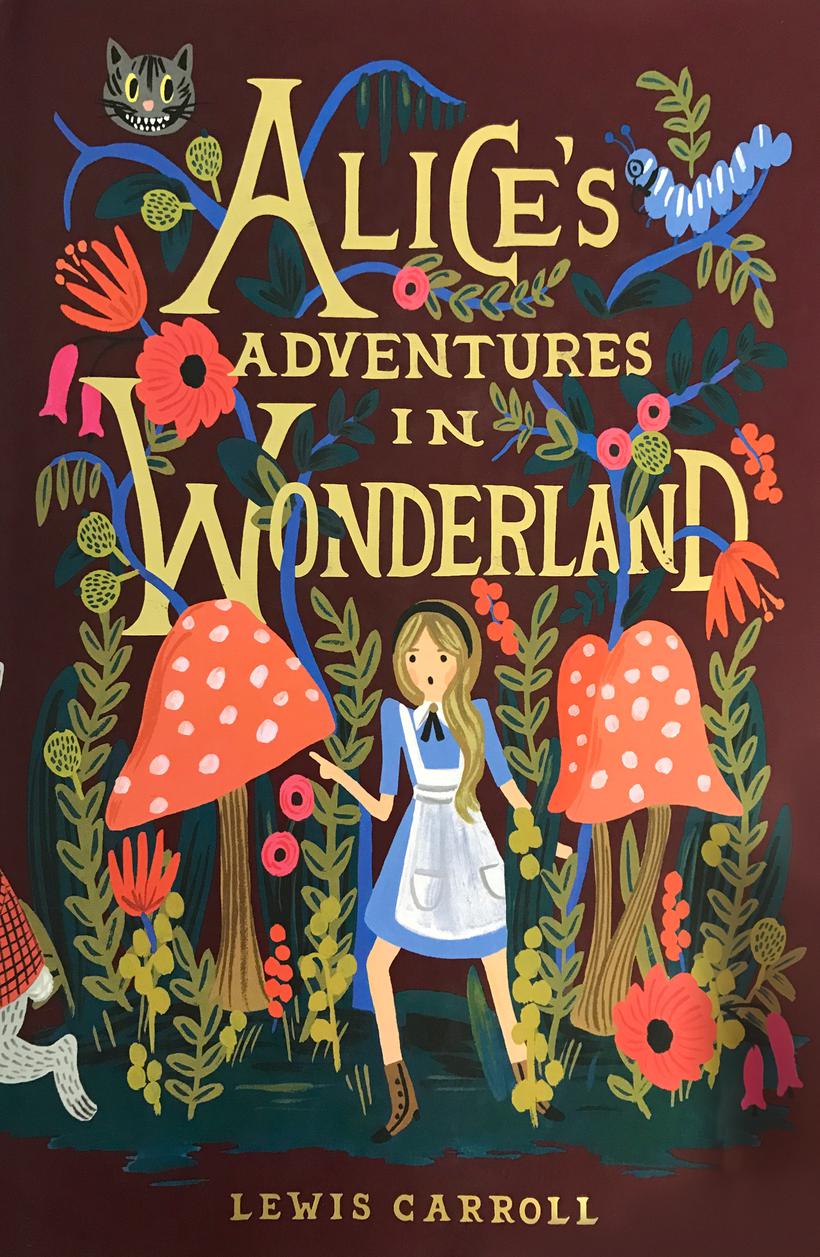

EmmaJane Austen

|

|

First Publication: December 23, 1815 Category: novel/comedy of manners Sales: ? |

Accolades:

|

|

About the Book: “Virginia Woolf called Jane Austen ‘the most perfect artist among women,’ and Emma Woodhouse is arguably her most perfect creation.” BN “Before she began the novel, Austen wrote, ‘I am going to take a heroine whom no one but myself will much like.’” WK “The main character, Emma Woodhouse, “is spoiled, headstrong, and self-satisfied.” WK She is “a young girl from a good home that does not need the financial support of a husband and is determined not to marry.” AZ She is a “thoroughly self-deluded young woman who has ‘lived in the world with very little to distress or vex her.’” BN This doesn’t deter her from playing matchmaker for the locals in the “fictional village of Highbury and the surrounding estates of Hartfield, Randalls, and Donwell Abbey.” WK. However, she “is blind to the dangers of meddling in other people’s lives; and her imagination and perceptions often lead her astray.” WK At the same time, she considers herself “herself impervious to romance of any kind” BN and “refuses to recognize her own feelings for the gallant Mr. Knightley.” BN “What ensues is a delightful series of scheming escapades in which every social machination and bit of ‘tittle-tattle’ is steeped in Austen's delicious irony.” BN “Emma, the last novel completed and published during Austen’s life, WK is her “most cleverly woven [and] riotously comedic” BN work. “As in her other novels, Austen explores the concerns and difficulties of genteel women living in Georgian–Regency England; she also creates a lively comedy of manners among her characters and depicts issues of marriage, gender, age, and social status.” WK Resources and Related Links:

|